From Avoidance to Action: What a Systematic Review Taught Me About Motivation and Behaviour Change at Work

- Elevation Occ Psy

- May 20, 2025

- 9 min read

Updated: May 25, 2025

One of the most persistent behavioural challenges I’ve encountered in organisational life is this: we avoid the conversations that matter most.

As someone deeply curious about the psychology of difficult conversations (DC), why we hesitate, why it’s hard, and what helps us take that courageous step, I wanted to dig deeper.

As part of my PhD research into difficult conversations (DC), and through both practice and observation, I came to a critical insight: motivation is often the primary driver in whether someone avoids or engages in a difficult conversation. This observation, grounded in both theory and real-world experience, led me to explore how motivation operates more broadly within workplace behaviour, and what techniques organisations are using to effectively influence it.

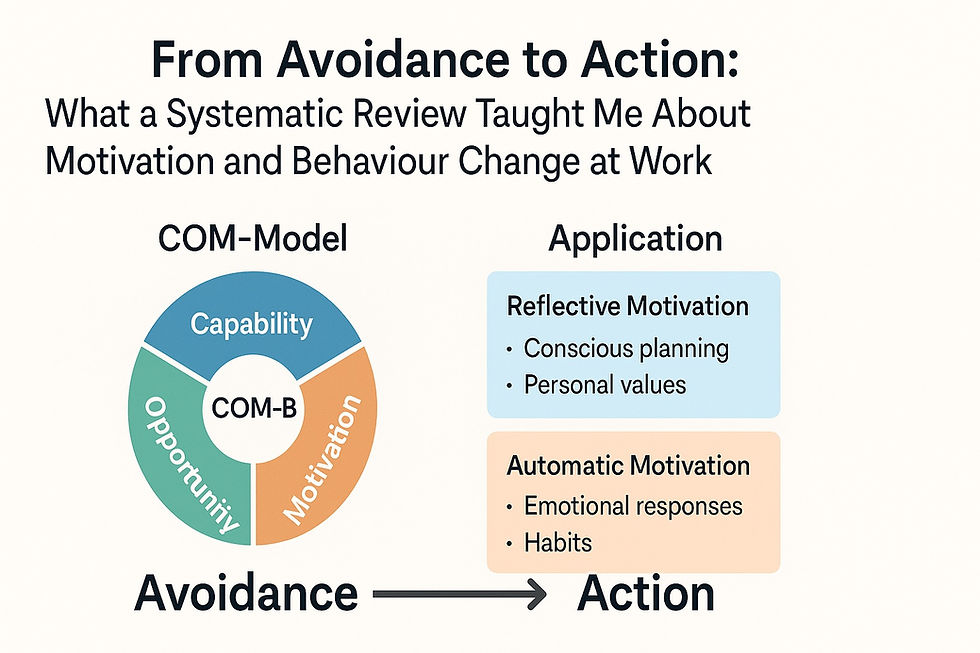

To answer that, I conducted a systematic literature review focused on motivation-based interventions grounded in the COM-B model of behaviour change. The goal? To identify techniques used effectively in organisations that could also be applied to shifting DC behaviour, from avoidance to action.

What is the COM-B Model?

The COM-B model (Capability, Opportunity, Motivation, Behaviour) provides a practical framework for understanding behaviour change. It also forms the core of the Behaviour Change Wheel (BCW), a tool that links behavioural analysis to evidence-based intervention strategies.

Within COM-B, motivation is categorised in two forms:

Reflective motivation: Conscious processes such as goal setting, planning, evaluation, and aligning actions with personal values

Automatic motivation: Habitual or emotionally driven behaviours, such as responses to cues, social norms, or reinforcement

The BCW suggests specific intervention functions that are most effective in targeting motivation:

For reflective motivation:

Education (increasing knowledge)

Persuasion (using communication to stimulate action)

Incentivisation (creating expectations of reward)

Modelling (showcasing desired behaviours through others)

For automatic motivation:

Training (improving skills or habitual responses)

Incentivisation (reinforcing behaviour through rewards)

Environmental restructuring (altering the physical or social context to support desired behaviour)

Enablement (removing barriers or enhancing means to act)

Many workplace interventions over-rely on reflective strategies like coaching or awareness-raising, without addressing automatic processes, despite growing evidence that habit, cues, and reinforcement are critical for sustained behaviour change.

Applying COM-B to Difficult Conversations

My interest in difficult conversations isn’t theoretical, it’s practical. These are the moments that define teams, shape cultures, and build trust. Yet they are also moments most people fear or delay.

What the review showed is that COM-B offers a powerful lens to reframe this challenge:

Reflective strategies, such as goal setting, feedback models, or values alignment, can support intention and skill-building

Automatic strategies, such as prompts, environmental cues, and social norms, can turn emotionally fraught action into routine, supported behaviour

So if we want to help people move from avoiding difficult conversations to having them, we must treat DC as a behaviour change challenge, and use motivation-based techniques accordingly.

Key Findings from the Review

I conducted a systematic review of 15 empirical studies examining motivation-based behaviour change interventions in organisational settings. These studies spanned diverse sectors, including healthcare, policing, corporate offices, and the gig economy, and drew on both qualitative and quantitative methods.

The search strategy combined terms across four domains — motivation, intervention types, workplace context, and behavioural outcomes, using Boolean logic. The final search string was:

("COM-B" OR "behaviour change model" OR "behaviour change wheel" OR "theoretical domains framework" OR "motivational component" OR "reflective motivation" OR "automatic motivation" OR "intrinsic motivation" OR "extrinsic motivation") AND ("behaviour change intervention" OR "motivational intervention" OR "goal setting" OR "habit formation" OR "values alignment" OR "coaching" OR "feedback" OR "self-determination" OR "incentive") AND ("workplace" OR "organisation" OR "occupational setting" OR "employees" OR "staff") AND ("behaviour change" OR "employee behaviour" OR "motivational outcomes" OR "habit change" OR "adherence" OR "performance improvement")

After importing results into a reference manager, I applied a structured three-stage screening process:

Title and abstract screening to remove clearly irrelevant or duplicate records

Full-text review against predefined inclusion criteria (e.g. workplace focus, motivation component explicitly addressed, empirical design)

Data extraction and quality appraisal using appropriate tools (e.g. Cochrane, CASP, MMAT)

This process filtered down several hundred initial results to a final sample of 15 studies that met all inclusion criteria and offered sufficient detail on intervention content, motivational mechanisms, and outcomes for in-depth analysis.

What emerged was a consistent pattern: interventions that targeted both reflective and automatic forms of motivation were the most effective in producing meaningful and sustainable behaviour change.

1. Integrated motivational strategies were consistently more effective

Interventions that intentionally addressed both reflective motivation (e.g. intention, planning, values) and automatic motivation (e.g. habit, emotion, environmental cues) yielded the strongest outcomes. These strategies created layered behaviour change, supporting both conscious decision-making and the formation of long-term habits. For example, combining goal setting with real-time habit prompts helped bridge the gap between intention and action.

2. Reflective-only strategies helped initiate change, but often lacked staying power

The majority of interventions reviewed relied heavily on reflective strategies, such as coaching, planning tools, or values alignment exercises. While these approaches were effective in building intention and raising awareness, they often fell short in producing sustained behavioural change without reinforcement. This mirrors common organisational experiences, where post-training drop-off is widespread once initial motivation fades.

3. Automatic motivation techniques are underused but powerful

Only a small subset of studies explicitly targeted automatic motivation, using tools like gamification, prompts, or environmental nudges. However, these interventions showed strong potential to support consistent behaviour, especially in repetitive tasks or emotionally charged behaviours, like following protocols, building new habits, or, potentially, engaging in difficult conversations. Their underuse suggests an important gap in current practice.

4. The most effective interventions were multi-component and theory-driven

Success wasn’t about any single technique. The most impactful interventions used a combination of Behaviour Change Techniques (BCTs) that targeted different aspects of motivation, often integrating reflective and automatic components into a coherent framework. Common combinations included:

Goal setting and planning — to help individuals define clear intentions and take ownership of change

Feedback and self-monitoring — to provide ongoing reinforcement and visibility into progress

Habit cues and prompts — to build automaticity and reduce reliance on willpower or motivation alone

Environmental restructuring — to make desired behaviours easier, more visible, or more rewarding

Values-based coaching — to enhance intrinsic motivation by linking behaviour to purpose and identity

This layered approach aligns closely with the Behaviour Change Wheel’s recommendation to design interventions that address multiple behavioural drivers, not just awareness or capability, but the motivation to act and keep acting.

What This Means for Difficult Conversations

One of the clearest insights emerging from my PhD research and systematic review is this: motivation is often the deciding factor between avoiding a difficult conversation and choosing to engage in one. And if that’s the case, then helping people “get better” at difficult conversations isn’t just about providing skills — it’s about designing environments, supports, and interventions that enhance motivation in a sustained way.

The COM-B model offers a powerful structure for understanding this, by showing us how both reflective and automatic motivation play a role in behaviour, and how we can intervene accordingly.

Build Reflective Motivation

Reflective motivation refers to the deliberate, conscious drivers of action, such as intentions, goals, and personal values. In the context of difficult conversations, reflective motivation might include wanting to uphold fairness, act with integrity, support a colleague, or resolve a tension for the sake of team performance.

To strengthen reflective motivation:

Link difficult conversations to core values: Help individuals understand how engaging in honest, respectful dialogue supports what matters most to them and the team, such as trust, clarity, or collaboration.

Use coaching, peer discussion, or structured planning: Techniques like motivational interviewing or reflective goal setting can help people articulate not just what they want to do, but why it matters to them.

Set measurable goals for speaking up: Encourage people to make small, trackable commitments (e.g. “give feedback once this week”) and reflect on the outcome, building motivation through evidence of impact.

Reflective strategies are especially useful for helping people overcome initial resistance, to consciously shift from avoidance to intention.

Support Automatic Motivation

Automatic motivation refers to the non-conscious processes that influence behaviour, such as habits, emotional reactions, social norms, or environmental cues. In many organisations, avoidance of difficult conversations becomes habitual, fuelled by unspoken norms like “don’t rock the boat” or emotional triggers like fear or discomfort.

To shift these automatic patterns, we can:

Embed prompts and rituals that normalise open dialogue, such as weekly “courageous conversation” slots, team reflection rounds, or rotating peer feedback check-ins

Gamify the behaviour: Use team-based incentives or recognition for practising honesty, respectful disagreement, or supportive confrontation

Restructure the environment to encourage conversational risk-taking, this could be as simple as leader-led modelling, discussion guides at meetings, or physical cues like conversation starters on the walls

Use behavioural nudges: Subtle prompts such as digital reminders, anonymous reflection tools, or visible commitment pledges can reduce friction and lower the emotional threshold for taking action

Automatic strategies help sustain behaviour, especially when emotional discomfort or workplace culture would otherwise cause people to retreat.

Design for Both: The Integrated Approach

The most effective way to enable difficult conversations is to design interventions that work across both motivational systems. This means:

Starting with values and intention (reflective)

Reinforcing through habit, cues, and environmental design (automatic)

For example:

A team might use values-based training to reflect on why open communication matters, followed by the introduction of weekly prompts to give or request feedback

An organisation might combine coaching support for leaders with visual cues and micro-rewards for employees who role model honest dialogue

Managers might use goal-setting and check-ins alongside tools that prompt action, like a ‘conversation planner’ embedded in meeting workflows

This layered approach acknowledges that motivation is not a one-off decision, but a dynamic process, and that people need ongoing support to build and sustain new behaviours.

Ultimately, if we want to move from a culture of silence or conflict avoidance to one of constructive, courageous communication, we must treat difficult conversations not just as a communication issue, but as a behavioural challenge grounded in motivation.

Motivation can be strengthened. Avoidance can be disrupted. And with the right structures, environments, and supports in place, action can become the norm, not the exception.

Implications for Organisations, Managers, and Employees

If we’re serious about improving communication, building trust, and creating cultures where difficult conversations are normalised rather than avoided, we need to shift our focus. Traditional training often treats communication as a skills deficit. But this research shows that avoidance is rarely a capability gap, it is most often a motivation gap.

And that gap is not accidental. It is shaped by organisational norms, leadership behaviours, emotional cues, and the (often invisible) habits that get reinforced daily. That means the responsibility, and the opportunity, to change doesn’t lie with individuals alone. It belongs to everyone, at every level.

For Organisations: Culture is Designed, Not Declared

Organisations must move beyond viewing difficult conversations as isolated soft-skills issues. These behaviours are systemically shaped, and so they must be systemically supported.

What organisations can do:

Invest in multi-layered, motivation-informed interventions: Programmes should integrate reflective techniques (like coaching or values alignment) with automatic strategies (like nudges, prompts, or environmental restructuring).

Audit cultural signals: Is your environment rewarding honesty and openness, or inadvertently reinforcing silence and avoidance? Assess what is implicitly valued — speed over clarity, harmony over truth?

Design for sustainability: Move away from one-off workshops and build feedback and conversation tools into daily workflows (e.g. check-ins, 1:1 templates, reflection rituals).

Model from the top: Executive and senior leaders must normalise discomfort, share how they approach difficult conversations, and reward transparency, not just outcomes.

For Managers: You Set the Tone

Managers are the frontline of culture. The way they respond to challenge, feedback, or dissent directly influences whether others feel safe to speak up or stay silent.

What managers can do:

Create psychologically safe routines: Don’t wait for conflict. Embed regular spaces for honest reflection, weekly team health checks, round-robin feedback, open forums.

Use motivation techniques in your leadership: Combine goal-setting for open dialogue with subtle prompts (e.g. “What tough thing needs to be said today?”), and reward the behaviour you want to see.

Reframe difficult conversations as learning moments: Make it clear that speaking up isn’t a threat to status or harmony, it’s a signal of care, accountability, and growth.

Support, don’t just instruct: Equip your team with language, tools, and frameworks to have hard conversations well. Offer coaching and space to practise.

For Employees: Action Starts with Awareness

Employees are not passive recipients of culture, they help shape it every day through what they speak up about, what they tolerate, and how they respond to discomfort.

What employees can do:

Reflect on your own motivation: What’s holding you back, fear, habit, a lack of clarity on how to start? Use tools like goal-setting or journaling to uncover your blockers.

Seek small wins: Difficult conversations don’t need to be dramatic. Starting with a low-stakes feedback or check-in builds confidence and builds habit strength over time.

Use your values as fuel: Reconnect to what matters most, fairness, trust, growth. When you link your actions to your personal and professional values, motivation increases.

Ask for structure: If your environment isn’t making it easier to speak up, raise that. Ask for tools, prompts, reflection sessions, whatever helps normalise these behaviours.

The Bigger Picture: Reframing Behaviour Change

This research reinforces a powerful shift in how we understand and support behaviour at work. Rather than treating communication breakdowns as individual failings, we can view them through the lens of behavioural science, and design environments that support the courage to act.

Whether you're an executive, a team lead, or an individual contributor, the message is clear:

If we want to turn avoidance into action, we must treat motivation not as an accident — but as something we can intentionally shape.

The tools are available. The evidence is growing. Now is the time to design for the conversations that matter most.

What’s Next?

This research is just one step in a broader journey, one that aims to make difficult conversations easier, safer, and more embedded in organisational life. I’ll be exploring how to translate these findings into practical tools and interventions that any team can adopt.

Let’s Talk: What’s helped you, or your team, move from avoiding tough conversations to embracing them? Have you seen motivation-based techniques work in action?

Comments